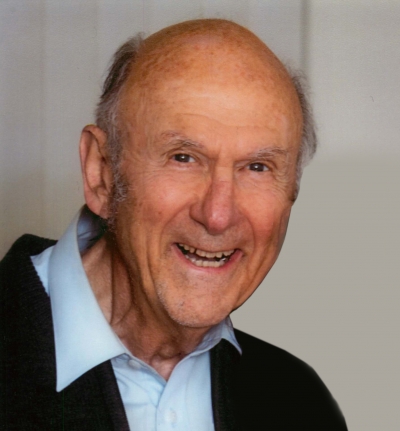

Herman Ohme

Jan. 12, 1925-Dec. 14, 2016

Palo Alto, California

Herman Ohme died peacefully on Dec. 14, just shy of his 92nd birthday. He had lived in Palo Alto since 1970, moving with his family from Los Angeles to accept a position as Principal of Cubberley High School.

Herman Ohme was born on Jan. 12, 1925, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to Esther and Harry Steinberg. He and his older sister Diana, and younger brother Nate, grew up in the small Jewish community of Squirrel Hill. His given last name was also Steinberg, but he changed it to Ohme after experiencing anti-Semitism in the army.

Herman was a deep thinker and lived by a set of humanitarian principles shaped by his ability to extract valuable lessons from every encounter. A graduate of Taylor Allderdice High School in Squirrel Hill, he always lived by the school’s motto: “Know Something, Be Something, Do Something!”

As a teenager, Herman volunteered at the Irene Kaufmann Settlement House in Pittsburgh, where he earned a scholarship for his efforts. Like most teenagers, he couldn’t wait to leave home and used his scholarship to enroll at Pennsylvania State University. But World War II was soon at hand, and the call to enlist was a call to adventure for Herman.

He enlisted when he was 17, lying about his age, but no one was asking. He was eventually transferred to Europe, and went to Normandy only days after the invasion. As a medic and very sensitive person, he was undoubtedly scarred for life by the horrors he witnessed. Sadly, he was never diagnosed or given the help he needed in making sense of the senseless.

Immediately after the war, he married a Parisienne and they had a son, Denys. The marriage ended soon after in divorce.

During the war, Herman wrote home often, and we recovered his box of wartime letters. In one letter, dated Aug. 13, 1944, he relayed a story that affected him profoundly. Still in France, he and a buddy were in search of a place to wash their clothes and came to a small village. They happened upon a woman and her twenty-something son, who were unpacking a crate. The crate contained a collection of family valuables, buried and hidden from the Germans who had occupied their home.

Eager to practice his French, Herman began a conversation with the young man and learned that he was a resistance fighter. Even with his broken French, these two men of different worlds were soon exchanging ideas and life philosophies. Herman was so touched to learn that the young man was not bitter or vengeful toward the Germans. Instead, this man, who as Herman wrote, “had fallen into the pitfalls of a modern war” was more determined than ever to forge a peaceful status among nations by treating everyone, even his prior oppressors, with the humanity and dignity expected of civilized peoples. To Herman, this “was a truly great man - a man who has learned the secret of eternal brotherhood.”

Many was the time that Herman put these principles into action, but the most memorable was 50 years later, when his car was stolen. Punishment and retribution were never high on Herman’s list, and he seized the opportunity to help transition a life with nothing to lose into one of hope and promise. Instead of pressing charges, Herman helped the young man enroll at Foothill College and even gave him some cash for books. Rather than exacting a pound of flesh, Herman believed that opening doors to learning was the only reasonable path – not only for the young man, but in the grand scheme of things, for all of us.

When he returned from the war, Herman moved west, and used the GI bill to attend UCLA, where he continued to study French. Soon he was teaching at UCLA, and his best friend’s sister from Squirrel Hill, Jean Magidson, turned up in his class. Their romance blossomed instantly, and they married in 1951. The couple bought a tiny post-war house in Mar Vista, on the west side of Los Angeles. There they had three children -- Rhonda, Karen and Steven.

In addition to his passion for education, Herman also had an artistic side. In the 1950s he designed a beautiful chess set, and his first career was an attempt to make a living at selling his unique sets. Chess set production was rewarding, but with a family to feed, chess became a hobby, and he returned to his first love, education.

Herman was a passionate educator and brought creativity, innovation and compassion to his lifelong career in education. Embracing his calling, he quickly rose through the ranks of the public education system -- first as a French teacher at Fairfax High School, finally securing his first administrator position as Vice Principal of Culver City High School.

On his first day as Vice Principal of Culver City High, he was given a stack of detention slips to “deal with.” He was flabbergasted to learn that the stack had been carefully preserved and carried forward from the previous school year. He noticed that these unfortunate souls had so many detentions (if you don’t serve your detention, you are punished with more) that they couldn’t live long enough to serve out their “sentences.” Herman wondered how these students could ever succeed when starting out so far behind on the first day of school. His first act as the new Vice Principal was to drop every last detention slip in the circular file and declare “amnesty for all!”

He continued moving up the education ladder while simultaneously pursuing and earning his Doctorate in Education from USC. In 1970, Herman accepted a position that turned out to be the crown jewel in his public service career -- Principal of Cubberely High School. Herman inherited a school that had been tumultuous in the 60s and was searching for new footing. With his love of learning and excitement to be in a community that revered education as much as he did, he accomplished great things at Cubberley, including having started an Alternative School on the Cubberley campus, to accommodate students who loved learning but needed a different approach. His years at Cubberley were his golden years, and even after leaving, he continued to host reunions for the faculty for many years to come.

After retiring from public service, Herman wrote articles and books about education and worked with his wife Jean, whose tutoring business was flourishing so much that it wound up becoming a full-fledged school. Working with Jean, Herman counseled students who had all but given up on school, because of debilitating failures in their short academic histories. When he met with these students and their parents, he asked probing questions and quickly found their gifts. He made every student feel smart and valued within only a few minutes of meeting them. He showed students how to get back on track and gave them the opportunity to learn at their own pace, to repeat failing grades, and to become confident students again. There was no greater joy for Herman than to watch students rekindle their hopes and dreams with a fresh start in school.

Herman’s father instilled in him that he was put on this earth to make a difference. Herman offered confidence, inspiration, wisdom, hope and dignity to everyone he encountered. He touched many lives, and there is no doubt that he did make the world a better place.

Although his cognition was severely impaired in the last years of his life, the family was comforted to know that Herman finally found peace in a loving place where he was well-cared for. He forgot his demons of the past, and he no longer struggled with the challenges of day-to-day life in his compromised state. We are grateful for the excellent care he received at Palo Alto Commons.

He is survived by his wife Jean Ohme; his sister Diana Leventer; his children Rhonda Racine, Karen Hobbs and Steven Ohme; his son Denys Ohme from a previous marriage; 6 grandchildren and a great-grandson.

Tags: teacher/educator